Kamaach (El Pilón de Azúcar). Foto: Juan Guillermo Sánchez M.

(READ THE ENGLISH VERSION BELOW)

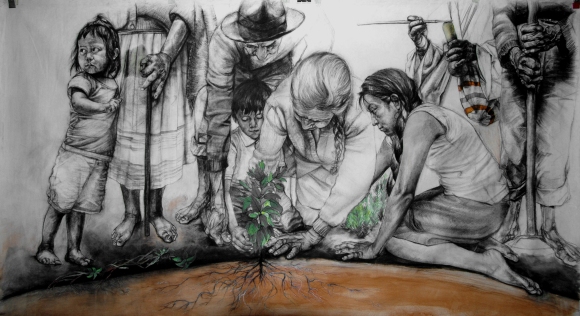

Nuestra invitada hoy es Woumain, la Guajira Wayuu entre Colombia y Venezuela, y su lucha por el Agua y el territorio contra la empresa transnacional de carbón El Cerrejón. Para ello, queremos recomendarles el documental Mushaisha, una pesadilla wayuu de Carlos Mario Piedrahita y Juan Sebastián Grisales (Premio Nacional de Periodismo Simón Bolívar 2014), así como varios textos de escritores wayuu.

Actualmente, los canales de televisión en Colombia, así como las redes sociales en el mundo, pasan documentales sobre la hambruna, la sequía en Woumain, y la muerte de niños Wayuu por inanición. Por primera vez, tal vez en siglos, las personas de las grandes ciudades se están preguntando qué es la Guajira Wayuu. Sin embargo, debido a la delicada situación política y social, los medios de comunicación han fijado una imagen de sufrimiento que olvida la riqueza humana de la nación indígena más numerosa de Colombia. Si bien es cierto que el cambio climático no está permitendo que Jepirachi (los vientos del nordeste) traigan a su tío Juya (la lluvia) para que fecunde a Maa (la tierra), también es cierto que la codicia y la fractura socio-cultural es hoy el resultado de décadas de extractivismo y desplazamientos, en donde no solo El Cerrejón es responsable sino el estado colombiano.

La semana pasada, el poeta y lingüista Wayuu Rafael Mercado Epieyu fue entrevistado en el programa radial de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia “Desde la botica”. Allí, a las preguntas ¿Qué es la Guajira para su comunidad? ¿Qué está pasando en la Guajira? Rafa, gran amigo y colaborador del Mensaje Indígena de Agua, respondió con el siguiente relato:

Nuestro territorio, desde nuestra visión wayuu fundamentada en los relatos ancestrales que se encuentran en la memoria de nuestros abuelos, de nuestras abuelas.

La parte que en castellano se conoce como Alta Guajira, donde se encuentra la Serranía La Macuira, nosotros la denominamos Wüinpumüin, que traduce “Hacia los caminos de las Aguas”. Es ahí, en ese esenario geográfico, donde se encuentra el principio, el origen de la vida para nosotros los Wayuu, a partir del camino de las aguas: Wüinpumüin. Y en ese escenario existen unas deidades que guardan esos lugares sagrados, donde por primera vez brotó la vida, desde el mundo de las Aguas, desde el mundo de Juya, nuestro abuelo. Juya es lluvia, Juya es hombre en Wayuu, y por lo tanto es nuestro abuelo, es El lluvia que conoce el secreto de la vida, en sus principios. En esos lugares sagrados, ahí se encuentran nuestros abuelos, como los animales, el lugar de ojos de agua en esta serranía que se llama Macuira. Entonces la Serranía para nosotros es la serranía madre que cuenta el origen de nuestra cultura.

Y más acá, bajando, donde se encuentra ese paisaje hermoso, donde en todas las tardes y en las mañanas, y en los mediodías de todos los días, es donde se levantan los granos de arena a danzar con el viento que viene del mar, que viene de Palaa, Palaa nuestra abuela, la madre de los vientos. Es ahí, ese escenario, la parte desértica que muestran en los canales, la parte que no hay nada según la televisión colombiana. Para nosotros, ese escenario de danza de vientos con las arenas de la tierra, de nuestra madre tierra, tiene mucho significado, expresa pensamientos primigenios. En las horas de la tarde podemos presenciar y sentir la llegada del viento Rülechi, que viene todas las tardes a caminar del Sur y encontrarse en el cerro que hoy en día se conoce como El Pilón de Azúcar. Este cerro en wayuunaiki se llama Kamaach, el cerro antiguo, el cerro ancestral. Es un escenario en donde se encuentra Rülechi, el viento del Sur, con el viento del Norte, Jepirachi, estos hijos de nuestra abuela Mar, Palaa, se encuentran y dialogan.

Y con estos conceptos que solamente se encuentran en las voces de nuestro abuelos. Pero hoy en día esas voces han sido ignoradas, apagadas, y por eso es que se vende esa imagen de la Guajira desde la visión del blanco. Desde la visión del alijuna [no Wayuu], como no ve cosas que no tiene en su mundo, entonces lo ha denominado como un territorio vacío, sin ningún significado, sino más bien le da ese significado de miseria, de pobreza, pero para nosotros los Wayuu, tiene una riqueza de conocimientos.

Y antes de llegar a la Sierra Nevada [de Santa Marta] está el Río Ranchería. Ahí habitaba la deidad de la fertilidad, nuestra abuela, Perakanawa, pero hoy en día, con los tropiezos y el salvajismo del capitalismo, ha sido destruido su habitat, y nuestra abuela, la deidad de la fertilidad, se ha ido y ha abandonado su lugar. Por eso es que han escuchado seguramente ustedes manifestaciones con el desvío del Río Ranchería [propuesta de El Cerrejón]. Ese Río Rancería era el nido, era habitat de Perakanawa, la deidad, la culebra, la gran abuela, que llegaba y fertilizaba y llenaba de vida a todo ser viviente, desde la hormiga, el árbol más pequeño, el más grande, ahí vivía. Pero ahora con todo el salvajismo del capitalismo ha espantado esa deidad.

Entonces ahí, todo este escenario del departamento [de la Guajira], seguramente si preguntáramos a un hermano Kogui, a un hermano Wiwa, a un hermano Arhuaco, también nos contaría algo parecido….

Escuchar aquí la entrevista completa a Rafael Mercado Epieyu => http://unradio.unal.edu.co/nc/detalle/cat/desde-la-botica.html

En los últimos cuarenta años, El Cerrejón se ha referido a la Guajira como una “tierra subutilazada”, “vacante”, “baldía”, pasando por encima de 3000 años de historias y saberes que los Wayuu han adquirido en Woumain. En Bajo el manto del carbón, Chomsky, Leech y Striffler (2007) han explicado que el proyecto multinacional de extracción del carbón El Cerrejón comenzó en 1975 y, actualmente, tiene un contrato con el gobierno colombiano hasta 2034. Desde el inicio, las comunidades Wayuu de Chancleta, Patilla, Roche, Los Remedios y Tamaquito, así como la comunidad afrodescendiente de Tabaco, fueron desplazadas.

Foto: Notiwayu / las2orillas => http://www.las2orillas.co/el-cerrejon-el-drama-en-la-guajira/

Remedios Fajardo – reconocida líder Wayuu – ha explicado que los Wayuu no solo han sido desplazados de los lugares de extracción en la Media Guajira como Caracolí y Espinal (Municipio de Barrancas donde viván 350 wayuu) a causa de las acumulaciones de basuras y desperdicios tóxicos; sino también de Puerto Bolívar (a donde llega el tren y de donde es exportado el carbón), conocido por los wayuu como la Media Luna (en donde habitaban 750 wayuu para 1980); y más recientemente del parque eólico Jepirachi (controlado por las Empresas Públicas de Medellín), cuya producción energética solo beneficia al puerto mismo de El Cerrejón. Para Fajardo, además de hurgar las entrañas de los cerros, montañas, bahías y cementerios sagrados, lo más grave es que este proyecto desconoce la concepción wayuu del territorio:

Si ellos salen de sus tierras, el resto de vecinos no les permitirá asentarse en sus territorios, les preguntarán: ¿Por qué entregaron las tierras que juya (la lluvia) les dio? ¿Qué vienen a buscar ahora en nuestras tierras? Según la tradición del pueblo wayuu quien cede sus tierras para quedarse sin ellas, pierde status ante la comunidad, y pierde credibilidad para asumir responsabilidades comunitarias. (Bajo el manto del carbón 22)

Señores Multinacionales, la nación Wayuu no está sola, la Guajira no está baldía, y el Mensaje Indígena de Agua se solidariza con los líderes, escritores, activistas y con las comunidades que están defendiendo en primera línea a Woumain! Es tiempo de dejar tranquilo el carbón en las entrañas de Mma.

Hasta la próxima semana.

***

“Toward the Paths of the Waters”: From Uchumüin To Wüinpumüin

Jepira (Cabo de la Vela, Guajira, Colombia). Picture: Juan Guillermo Sánchez M.

Our guest today is Woumain, the Wayuu Guajira between Colombia and Venezuela, and its fight in defending the Ranchería River and the Bruno Creek from the transnational coal mine El Cerrejón. In order to contextualize this long struggle, we would like to share some literary texts by contemporary Wayuu writers.

Railroad from El Cerrejón Mine to Puerto Bolivar (Bolivar Port). Map: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2016/02/life-latin-america-largest-open-pit-coal-160201114829811.html

Currently, Colombian mass media and virtual social networks are reproducing news and documentaries on Woumain’s hunger, drought, and the deaths among Wayuu children because of dehydration and starvation. For the first time in centuries, the people in larger cities of South America, or where the South American diaspora is, are interested in the Wayuu Guajira. However, because of the complex social and political situation of the region, the mass media has portrayed a broken image, which sometimes forgets the human richness of the biggest indigenous nation in Colombia. While it is true that global warming has prevented Jepirachi (the winds from the northeast) from bringing their uncle Juya (the rain) to fecundate Mma (the earth), it is also true that today’s greed and social imbalance are the consequences of decades of mining and displacement, for which not just El Cerrejón is responsible but also the Colombian government.

El Cerrejón, the largest open-pit coal mine in the world, owned by BHP Billiton, Anglo American and Xstrata/Glencore.Picture: lachachara.org

On May 5th, the Wayuu poet and linguist Rafael Mercado Epieyu was interviewed in the National University’s radio program “Desde la botica”. To answer the questions “What does the Guajira mean to your community?” and “What is happening in Guajira?”, Rafael, a great friend and contributor of the Indigenous Message on Water, shared the following story:

Our territory, from the Wayuu vision, is founded in the ancestral stories, which are placed in the memory of our grandfathers and grandmothers. The place which is known in Spanish as Alta [Upper] Guajira, where the Macuira Mountain range is, we call it Wüinpumüin, which translates as “Toward the Paths of the Waters”. It’s there, in that geographical scenario where the beginning is, the origin of life, the Paths of the Waters: Wüinpumüin. So, in that scenario there are some deities who keep those sacred places, where, for the first time, life bloomed—from the Waters’ world, from the Juya’s world, our grandfather. Juya is rain, Juya is man in our language, therefore He is our grandfather, He is who knows the secret of life, in its principles. It is in those sacred places that our grandparents can be found, like the animals, the eyes of water in that mountain range which we call Macuira. So, for us, this mountain range is our Mother who tells the story of our culture.

And you go down where that beautiful landscape is, where every afternoon and every morning, and every noon of everyday, the grains of sand dance with the wind, which comes from the sea, from Palaa, our grandmother, the mother of the winds. It’s there, in that scenario, the desertic part that the TV channels show, where there is nothing, according to Colombian television. For us, that place of dancing, between the earth’s sands and the winds, has a lot of meaning; it expresses original thoughts. In the hours before sunset we can witness and feel the arrival of Rülechi, who comes every afternoon, walking from the South to hit the hill, which is known today as El Pilón de Azúcar. This hill, in wayuunaiki, is called Kamaach, the old hill, the ancestral hill. That’s the scenario where Rülechi, the wind from the South, meets with the wind from the North, Jepirachi, both children of our grandma Sea, Palaa. They both meet with each other and dialogue.

And these concepts are only found in our grandparents’ voices. But, nowadays, those voices have been ignored, muted, and that’s why that image of the broken Guajira has been sold by the white men. Because if he does not see the things that he has in his world, the alijuna [non Wayuu] has named Guajira as an empty land, without meaning, giving it a connotation of misery and poverty. But, for us, the Wayuu, the same land is rich in knowledge.

And before one hits the Sierra Nevada [de Santa Marta], there is the Ranchería River. The fertility deity used to inhabit there, our grandmother, Perakanawa, but nowadays, with capitalistic savagery and setbacks, its habitat has been destroyed, and our grandmother, the fertility deity, has gone and abandoned her place. That’s why you have probably heard protests against El Cerrejón’s proposal to change the course of the Ranchería River. The Ranchería River was the nest, the Perakanawa habitat, the deity, the snake, the great grandma, who used to come to fertilize and fill every single being with life from the ant to the biggest tree. She used to live there. But now, all the capitalistic savagery has frightened that deity.

So this is the scenario of the Guajira province. Probably, if we talk to a Kogui brother, a Wiwa brother, or an Arhuaco brother, they would say something similar…

Listen here the complete interview to Rafael Mercado Epieyu (in Spanish)=> http://unradio.unal.edu.co/nc/detalle/cat/desde-la-botica.html

In the last forty years, El Cerrejón has called the Wayuu Guajira an “under-used land”, “vacant”, “empty”, stepping on 3000 years of history and knowledge which the Wayuu nation has built on Woumain. In Bajo el manto del carbón (The People Behind Colombian Coal), Chomsky, Leech and Striffler (2007) have explained that the multinational project of coal extraction El Cerrejón, started in 1975, has a contract with the Colombian government until 2034. From the beginning, the Wayuu communities of Chancleta, Patilla, Roche, Los Remedios, and Tamaquito, as well the Afro-Colombian community of Tabaco, were displaced.

Remedios Fajardo, renowned Wayuu leader, has also explained that the repercussions of El Cerrejón’s projects extend beyond the extraction points of the middle Guajira, such as Caracoli and Espinal, where 350 Wayuu were displaced due to piles of garbage and toxic waste. Puerto Bolivar, furthermore, the train arrives and the coal is exported to Europe and the US, has seen the displacement of 750 Wayuu people. More recently, Wayuu people have been displaced from the Jepirachi Wind Turbine Project, controlled by the Medellin Public Enterprises (EPM), whose energy only benefits El Cerrejón´s port. According to Fajardo, in addition to digging the hills’, mountains’, bays’ and cemeteries’ guts, it’s clear that those projects don’t understand the Wayuu territory:

If the displaced Wayuu leave their lands, the rest of the community won’t permit them to settle in their lands. They will ask them: Why did you give away the lands that Juya, the rain, gave you? What are you looking for in our land? According to Wayuu nation’s tradition, those who give up the land stay landless, lose status among the community, and lose the trust in assuming community responsibilities. (Bajo el manto del carbón 22)

This situation, of course, divides the community, and it ends up being an advantage for the purposes of the multinationals. Meanwhile, with the virtual advertisement of “social responsibility”, “green energies” and cultural programs, as the EPM celebrates in its website, El Cerrejón distracts the attention from the local issues and violates indigenous rights.

Watch here “The Survival of the Wayuu People” by PBI Colombia (2012) => https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rs6cGKx6Kdo

As a sovereign response, the Woumain’s literary production is pioneering in the history of indigenous literatures from the Abya-Yala. In March, 2011, the Wayuu writer Estercilia Simanca Pushaina published in her blog “Daño emergente, lucro cesante” (“Emerging Damages, Lost Profits”), a short-story about a Wayuu woman who every Monday crosses El Cerrejón’s railroad with her donkey Mushaisa. The narrator says:

…He [the donkey] and I never got accustomed to the train, and I believe that the people on the other side, in the village, never did either—neither the goats nor the children, nobody in this place. Since I have memory, he [the train] was here, crossing the Peninsula from Uchumüin –South- to Wüinpumüin –North-. People say that he arrives to the sea, and that a big ship comes and takes the coal that the train brought, and then the train returns to look for more coal, digging the guts of Mma, the earth, She who keeps the blood of our birth, and the navels of the newborns. My tata says that the cemeteries of a lot of families are where the train passes, but the train didn’t care because he had to pass that way. The bones could simply be carried from one place to other, and a new cemetery could be built, more beautiful and whiter than the other. But, the train couldn’t make another path, NO! He had to pass that way, and that’s it, you know…, that’s it, the train is still passing everyday and Mondays, in the morning… (read the complete story in Spanish here)

As in all of the posts of the last few weeks, Simanca summarizes an old tension in Woumain, a confrontation between two mindsets, two ways of understanding nature and culture: on one side, the “progress locomotive” and the mining paradigm; on the other side, the resistance of native and peasant communities in defending their territories, their cemeteries, sacred places, livestock, plants, and sovereignty.

Please read this wonderful article by Robert Llewelyn, “Across Colombia by train, with García Márquez”, published in Political Newsletter Counterpunch. (December 26-28, 2014) => http://www.counterpunch.org/2014/12/26/across-colombia-by-train-with-garcia-marquez/

A year after “Emerging Damages, Lost Profits”, on March 7th, 2012, the Wayuu poet Miguel Ángel López-Hernández, also known as Vito Apüshana, published an open letter entitled “Señores Multinacionales” (“Mr. Multinational”) in the Colombian newspaper El Tiempo, in which he also refers to this rivalry between the “progress locomotive” and the ancestral knowledge:

We know that our spirituality, which you call romanticism, is the worst enemy of business; that’s why we don’t expect you to agree with us, we just want to make evident the proportion of your thirst for profit, the size of your disasters, and the final disproportion of your responsibilities.

We compare the weight of your shiny names with the effects on the lands you will devastate: Greystar Gold = stone dust of Santurbán; El Cerrejón = Ranchería River’s steam; MPX (Brazil) = hollow of the green Perijá (Guajira); Anglo Gold Ashanti = sterile slopes of La Colosa (Tolima); Muriel Mining Corporation = poisoned waters of the Cara Perro Hill and Ellausakirandarra (Chocó); Brisa Group = wound in the Julkuwa Hill (Dibulla); Endesa (Emgesa) = Magdalena River’s hunger in El Quimbo (Huila)… among many others.

Large-scale mining is the creature that you have created to support the motion of the world, which, because of its infinite growing, will end up devouring itself, and then, the planet will collapse; the terrible creature who we fight and will fight with rogations of belonging, and songs of collective continuity by the rural inhabitants… songs interweaved from the Inuit’s ice in Canada to the Perito Moreno glaciers in the Tierra del Fuego. To this creature, we’ll say “No”, we’ll say “No more!” And our spilled blood, maybe, will be the last frontier. (Read the full letter in Spanish here)

Apüshana goes beyond Guajira, and sends his message against “the creature” in other latitudes of the Abya-Yala / Turtle Island. His argument puts together the local issue with the global need (post-racial?) for the survival of the humanity.

One month after this letter, Vicenta Siosi Pino, Wayuu writer from the Apshana clan, published “Letter from a Wayuu woman to the Colombian President” in the Colombian newspaper El Espectador, a text that traveled the world in defense of the Ranchería River, the only one that crosses Woumain (published also in the Indigenous Message on Water). Through the mass media, Siosi’s letter generated a national and international attention on the devastation it would cause El Cerrejón’s project of change the course of the river.

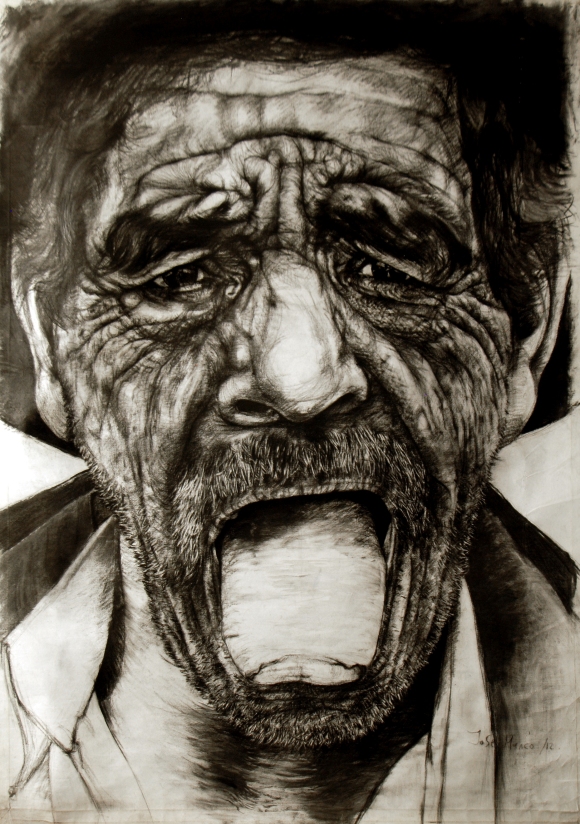

The same year Siosi wrote his letter, the poet and linguist Rafael Mercado Epieyu dedicated some poems to the El Cerrejón struggle. In “El tren no sabe detenerse” (“The train doesn’t know to stop”), Woumain is permanently deformed, and She cries while her children cough and the stubborn train, “the progress locomotive”, continues its noise and hurry:

¡shalerein! ¡shalerein! ¡shalerein!

That’s how the noise of the train feet sound

¡tününüin! ¡tününüin! ¡tününüin!

That’s how the earth’s whine sounds under its weight

¡ojo´o! ¡ojo´o! ¡ojo´o!

One can hear the Wayuu cough

Because of that black fine dust that the train emits

They breathe it, drink it, and the children’s skin melts

– Goats should not cross here,

the train does not know how to stop –

Those are the words written in their signs.

¡ja ja ja!

If the old Wayuu don’t know how to make those written words speak

Neither do the goats.

The land of the Wayuu is deformed,

now they are disgraceful to her.

They are well with the richness of its Guajira land.

That’s what people say to them.

Lie, we all know it!

Just a few days ago, due to the resistance of the Wayuu nation against the changing of the course of the Ranchería River, and because of the company’s rush to exploit a mineral that is loosing its power in the macro-economy of the global production of energy, El Cerrejón proposed to change the course of the Bruno Creek, tributary of the Ranchería River, but the response of the community was immediate (read the Manifesto in Spanish).

Dear Mr. Multinational, the Wayuu nation is not alone anymore. With this post, the Indigenous Message on Water shows solidarity with the leaders, advocates, writers and the communities who are defending Woumain in the front-lines! It’s time to leave the coal underground, in the Mma’s guts.

Until next week when we’ll close this cycle of thirteen posts!

***