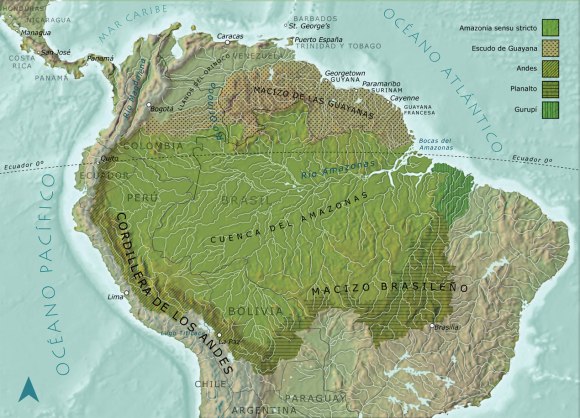

Amazonia. Map: http://www.imeditores.com/banocc/amazonia/mapas.htm

Amazonia. Map: http://www.imeditores.com/banocc/amazonia/mapas.htm

{LEA LA VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL ABAJO)

The Amazonia forest spans eight South American countries—Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela—and one foreign possession, French Guyana. Following our post about the Sarayaku’s legal victory in the Ecuadorian Amazon, today we would like to recommend the documentary People From the Amazon and Climate Change (2014), a testimony on indigenous ecoturism projects in two protected areas in the Peruvian Amazon: Amarakaeri Comunal Reserve, and Tuntanain Natural Reserve. Thinking about protected areas, we would like also to reflect on the Yaigoje-Apaporis Park in the Colombian Amazon, and the Makuna teachings about the minerals.

Watch People From the Amazon and Climate Change here => https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vIKKlIynklc

One always listens and reads about how the Amazonia is the lungs of the planet, however, in order to visualize its magnitude, we would like to underline some statistics. According to the National Geographic Magazine Climate Issue (November 2015):

There are 713 protected natural areas and 2467 indigenous territories in Amazonia. They cover 51 percent of the region—an expanse larger than India (…) A tenth of the world’s species are thought to live in Amazonia (…) Half the world’s tropical rain forests [Igapó, Várzea, and Terra firme] are found in Amazonia (…) Amazonia is a huge carbon sink. Its soil and vegetation hold roughly a fourth of all the world’s carbon that’s stored on land. But scientists say a tree die-off in the past decade is shrinking the region’s capacity to absorb the planet’s carbon. (NGO Climate Issue)

There is not doubt that there are global consequences from hurting the Amazon forest, but we need to acknowledge that indigenous peoples and local communities are the front-line defenders. Currently, as we learn from the protagonists of People From the Amazon and Climate Change, one of the main concerns of the Harakmbut and Matsigenka nations in the Amarakaeri Comunal Reserve, and the Awajun and Wachipaeri nations in the Tuntanain Natural Reserve, is on food security. Floods in the dry season, foreign fungus on the trees, unusual worms in the meat of hunted mammals, and displacement of species such as turtles and fish, are all symptoms of climate change that they have experienced. For Harakmbut Chief Walter Yuri, fortunately, they have the Amarakaeri Comunal Reserve where they can still get their medicines, meat, fish, and birds—the healthy foods of their diet.

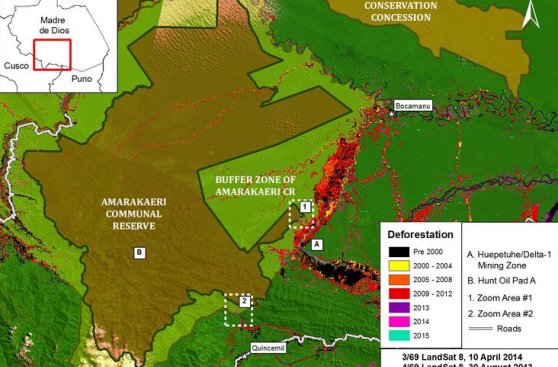

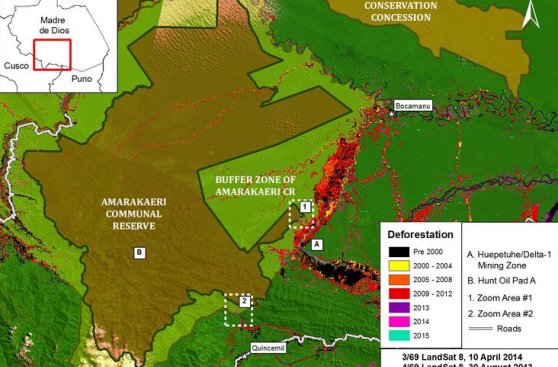

Deforestation around Communal Reserve Amarakaeri. Map: El Comercio

Deforestation around Communal Reserve Amarakaeri. Map: El Comercio

Nevertheless, as the “development projects” grow in the Amazonia, natural reserves and the people who inhabit the forest are being cornered. Felix López, from the Awajun nation, explains the impact of industrial forestry:

Speaking of climate change, there used to be a lot more timber trees, like tornillo, mahogany and cedar, and they help the crops grow, they fertilize it, but there aren’t any now. The loggers are exterminating the timber trees, and as there aren’t any trees anymore, the sun burns right down on the plant, and so it takes longer to grow, and it lacks fertilizer. (People From the Amazon and Climate Change)

Indeed, there are culprits of climate change. The detailed maps of the Amazon in the climate issue of National Geographic show the area’s richness in minerals such as gold, copper, and iron, as well oil and gas. But they also explain the consequences of deforestation, mega-dams, and mining (including roads and pipelines) in the ecological balance between the rainfall, the Andean spring waters, river flows, flooding season, and life:

Both [oil and gas] are economic mainstays of Ecuador and Peru. Today 107 blocks are producing oil and gas in Amazonia, most of them in the Andes [nearly nine-tenths]; 294 more potential blocks could mean more roads and more deforestation (…) The Amazon is the world’s largest river system. Hydropower supplies more than a third of Ecuador’s and Bolivia’s electricity and about a fourth of Peru’s. But deforestation is reducing rainfall and river flow, which also hinders fish migration between the mouth of the Amazon and the upper watershed. (NGO The Climate Issue)

In the Colombian Amazon, there is currently a paradox: after more than sixty years of civil war, nation-state government is in peace negotiations with the guerrillas, and as a result of this historical event, isolated provinces such as Vaupes, Caqueta, and Amazonia are in the sights of transnational and illegal mining. One example, among many (see the case of La Macarena Serrania), is the project of COSIGO Resources’, a Canadian mining company, in the Natural Park Yaigoje-Apapaporis, the sacred birthplace of the Macuna, Cabiyarí, Tuyuca,Tanimuca, Letuama, Yauna, Barasana, Yujup and Puinave nations.

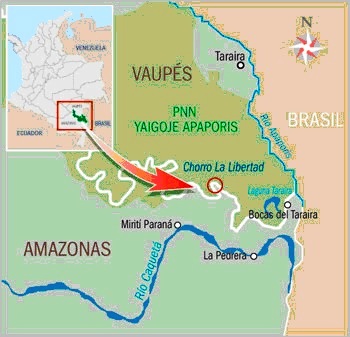

National Park Yaigoje-Apaporis. Picture: http://www.territorioindigenaygobernanza.com/col_14.html

The Apaporis area—between the Orinoco Great Plains and the Amazon forest—has been in the sights of colonial enterprises for centuries. The Apaporis forest resisted the thirst for quinine, curare (a natural sedative), and natural rubber during the 19th Century, and the slavery by the Tropical Oil Company in the 20th Century. As the renown journalist Alfredo Molano explains, one of the main reasons for this colonial failure has been the indomitable Apaporis River, the river of mirrors, full of waterfalls that make it impossible to navigate. According to the Makuna tradition, it was formed when the Tree of the Beginning fell and its trunk and branches created the river’s broken hydrography (read Molano’s article).

On October 27th, 2009, the Natural Park Yaigoje-Apaporis—a cultural and natural reserve of 1 060 603 acres—was created as an initiative of the Yaigoge Indigenous Chiefs Association (Aciya) with the support of the Colombian Ministry of Environment. The park is part of the “Gold Belt of Taraira”, which crosses Brazil and Colombia. As Alfredo Molano also explains in 2011, during Alvaro Uribe’s presidency, the Ingeominas, the Colombian institution that regulates mining, accepted 23 more applications to exploit gold in the park. Some of these applications were signed by Andrés Rendle, COSIGO’s vice-president for South America. The application process cost approximately 500 dollars, but when the license was approved, it could be sold for millions. On August 31st, 2015, the Colombian Court ordered to suspend any mining activity in the area. However, there is still uncertainty about what this company is planning to do with these mining titles, which are supported by international trade treaties (read “Indigenous Peoples of Yaigoje Apaporis Victorious as Court Ousts Canadian Mining Company”)

Beyond the legality or non-legality of the mining projects, and beyond Canadian or Colombian responsibility, there is an old confrontation between two different mind-sets, as we have addressed in the last few weeks. One of the main questions to start this conversation is: What does nature mean? Followed by: What does gold, oil or water mean? And, finally: Why are we consuming so much energy, and how can we change our habits? For the miner’s mind-set, nature is just a resource to be exploited. The COSIGO’s vice-president, Andrés Rendle, for example, thinks that the “Colombian noise” about their project is surprising. In his words: “It’s just a flea in the Amazon”. His discourse of clean technology and profit for Colombia is weak, particularly in the context of the statistics above. On the other hand, when the Elder Makuna Gerardo was asked about his point of view about mining, he said that the Makuna knew about those minerals, but didn’t touch them because they were always located in sacred areas:

Those minerals will cure the world. If one exploits them, they will bring consequences for the communities (read the full article)

Furthermore, the place that COSIGO is interested in is called Yuisi. And, according to the Pira River Chiefs, Yuisi “is where the energy that regulates and revitalizes life is concentrated”. Yuisi is the Jaguar Backwater, a sacred place for the Apaporis medicine men, a place not to be touched because it belongs to the underworld spirits. In this mind-set, completely contrary to the position taken by the Canadian mining company, nature has its own owners, people from the underworld and the Water people. Despite the mining companies disregard of this message, the first peoples of these forests clearly know what they are talking about.

In the Avina Foundation’s report about the impact of mining on Amazonia (read in Spanish full document here), we can find several testimonies of Chiefs, Elders, peasant miners, and Shamans from the Caqueta River, who have already suffered terribly from gold mining. Over and over, we can read the same comments: the mining projects bring the collapse of the family, prostitution, alcoholism, selfishness, illness, and death in the river produced by chemicals. After reading these testimonies it seems this collapse has an explanation in the traditional beliefs: gold, emeralds, quartz, and diamonds are the organs of our planet, they are also houses of spirits who know how to tie and control diseases. If someone breaks these shrines, these energies will ask a high price to compensate for the imbalance. There is a reason why these minerals are in specific places and not in others. This is one of the Elders’ comments about the Canadian Company’s project:

If we allow that the Canadian company exploits the gold where we consider there is a sacred place, a lot of problems will come: children’s disease and death, crimes among indigenous and white people, war between the guerilla and the army, prostitution, and in the end nobody will respect each other, nor the culture or the tradition. (Fundación AVINA 27)

Today, we would like to end our post with Leila Salazar-López’s words in Amazon Watch: Building Indigenous Alliances for the Climate:

We need more supporters. If we want to stop climate change, we have to protect the Amazon rain forest. It’s the lungs of the planet. And to do that, we have to support indigenous peoples’ rights” (watch documentary)

Until next week!

***

“Esos minerales son para curación del mundo”: Amarakaeri, Tuntanain, y Yaigoje-Apaporis

Parque Yaigoje-Apaporis. Foto: Colparques

La selva amazónica se expande a lo largo de ocho países suramericanos – Bolivia, Brasil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Perú, Suriname, y Venezuela – además de una posesión extranjera, la Guyana Francesa. Hoy, continuando con nuestro post sobre la victoria legal de la nación Sarayaku en la Amazonía ecuatoriana, queremos recomendar el documental People From the Amazon and Climate Change (2014), un testimonio sobre ecoturismo indígena en dos áreas protegidas de la Amazonía peruana: la Reserva Comunal Amarakaeri, y la Reserva Natural Tuntanaín. Además, pensando en estas áreas protegidas, queremos reflexionar sobre el Parque Yaigoje-Apaporis en la Amazonía colombiana, y las enseñanzas Makuna sobre los minerales.

Ver People From the Amazon and Climate Change AQUI => https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vIKKlIynklc

Siempre escuchamos y leemos que la Amazonía es el pulmón del planeta, sin embargo, para poder visualizar su magnitud, nos gustaría subrayar algunas estadísticas. De acuerdo al número sobre cambio climático de la National Geographic (Noviembre de 2015):

Hay 713 áreas naturales protegidas y 2467 territorios indígenas en la Amazonía. Estos cubren 51% de toda la región –una extension más grande que la de la India (…) Un décimo de las especies del mundo se cree que viven en la Amazonía (…) La mitad de las selvas lluviosas tropicales [Igapó, Várzea, y Terra firme] se encuentran en la Amazonía (…) La Amazonía es un disipador gigante de carbón. Su suelo y vegetación contienen aproximadamente un cuarto de todo el carbón del planeta guardado en la tierra. Pero los científicos dicen que la tala y la mortandad de árboles en la última década está reduciendo la capacidad que tiene de absorver el carbón. (Revista aquí)

Al herir la selva amazónica, no hay duda de que hay consecuencias globales, y ahora mismo necesitamos reconocer que las comunidades indígenas y locales que habitan esa selva son sus defensores de primera línea. Actualmente, como escuchamos de los protagonistas de People From the Amazon and Climate Change, una de las preocupaciones principales de las naciones Harakmbut y Matsigenka en la Reserva Comunal Amarakaeri, y las naciones Awajun y Wachipaeri en la Reserva Natural Tuntanain, es la seguridad alimentaria. Desde su propia experiencia, las inundaciones en el tiempo seco, los hongos no habituales en los árboles, los gusanos en la carne de los mamíferos, el desplazamiento de especies como tortugas y peces, son todas pruebas del cambio climático. Para el líder Harakmbut Walter Yuri, afortunadamente hoy ellos tienen la Reserva Comunal Amarakaeri, donde aun pueden obtener medicinas, carne, pescado, aves, y demás productos de su dieta. ¡Es como un supermercado¡, dice riendo.

Deforestación alrededor de la Reserva Comunal Amarakaeri. Fuente: El Comercio

Sin embargo, a medida que los “proyectos de desarrollo” crecen en la Amazonía, las reservas naturales y las comunidades que las habitan están siendo arrinconadas. Félix López, de la nación Awajun, explica el impacto de la industria forestal con las siguientes palabras:

Hablando de cambio climático, antes había muchos más árboles altos y perennes, como el tornillo, el mahogany y el cedro, y estos ayudaban a que los cultivos crecieran, ellos fertilizaban, pero ahora no hay ninguno. Las máquinas han exterminado estos árboles, y ya que no hay ninguno, el sol cae directamente sobre las plantas, entonces toma más tiempo para que crezcan, y hay falta de fertilizantes naturales. (People From the Amazon and Climate Change)

En efecto, el cambio climático tiene responsables directos. Los mapas detallados de la National Geographic que mencionábamos arriba, describen la riqueza de la Amazonía en minerales como el oro, el cobre, el hierro, además de los hidrocarburos. Estos mapas ilustran las consecuencias de la deforestación, las mega-represas, y la industria minera (incluidas sus carreteras y ductos) en el balance ecológico entre la lluvia, los manantiales de montaña, las corrientes, las inundaciones y la vida en la selva:

Ambos (gas y petróleo), son los pilares económicos de Ecuador y Perú. Hoy hay 107 sitios explotando gas y petróleo en la Amazonía, la mayoría de ellos en los Andes (casi 9 décimos); otros 294 potenciales sitios de explotación significarían más carreteras y deforestación (…) El Amazonas es el sistema de ríos más largo del mundo. Las hidroeléctricas suplen más de un tercio de la electricidad de Bolivia y Ecuador, y más o menos un cuarto de la de Perú. Pero la deforestación está disminuyendo la caída de agua lluvia y la corriente de los ríos, lo que a su vez impide la migración de los peces entre la boca del río Amazonas y las cuencas.” (Leer revista aquí)

Por su parte, en la Amazonía colombiana, hay una paradoja actual: tras más de sesenta años de Guerra civil, el gobierno nacional está ahora mismo negociando la paz con las guerrillas, y como resultado de este momento histórico, las regiones más apartados de los centros urbanos como el Vaupés, el Caquetá y el Amazonas, están en la mira de la minería transnacional e ilegal (leer aquí “La estrategia del despojo” de Alfredo Molano”).

Foto: Revista Semana. Audios e imágenes en “Parque Apaporis Mina” http://www.semana.com/especiales/parque-apaporis-mina/

Un ejemplo entre muchos (ver el caso reciente de la Serranía de La Macarena) es el de Cosigo Resources en el Parque Natural Yaigoje-Apaporis, el sagrado lugar de origen de la naciones Macuna, Cabiyarí, Tuyuca,Tanimuca, Letuama, Yauna, Barasana, Yujup y Puinave, entre otras. En la lengua yerar – según explica Alfredo Molano – “apaporis” significa “el centro del universo” y, al mismo tiempo, funciona como el verbo “transformar”. El caudal de su río, quebrado por continuas caídas de agua, ha dificultado por siglos que los colonos ingresen. Eso sin contar que desde los años ochenta ha sido uno de los epicentros del conflicto armado en Colombia. Por todo ello, el Apaporis ha sobrevivido a la sed de la quinina, el curare, el caucho, y la esclavitud de la Troco (Tropical Oil Company). Hoy otra “criatura” acecha el Apaporis: la urgencia de explotar el “cinturón de oro de Taraira” (escuche aquí la charla “Apaporis. Viaje a la última selva” de Alfredo Molano).

Hoy nos gustaría finalizar nuestro post con las palabras de Leila Salazar López en un documental sobre la reunion reciente en París sobre Cambio Climático, Amazon Watch: Building Indigenous Alliances for the Climate (2016):

Necesitamos más colaboradores. Si queremos detener el cambio climático, tenemos que proteger la selva húmeda amazónica. Ella es el pulmones de nuestro planeta. Y para protegerla, necesitamos apoyar a los pueblos indígenas en la defensa de sus derechos. (ver Amazon Watch: Building Indigenous Alliances for the Climate)

Hasta la próxima semana!