(LEA LA VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL ABAJO)

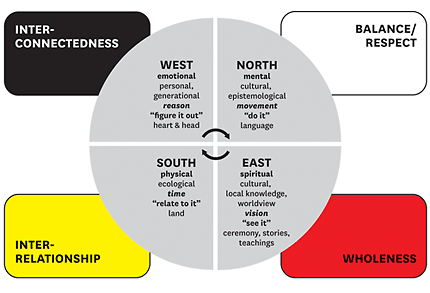

Today, we would like to close this cycle of posts with poetry and documentaries! In spreading intercultural awareness in the last thirteen weeks, we have been building bridges between the voices and the struggles to defend Water throughout Abya-Yala / Turtle Island. Today is a special day because we would like to share with you the vision behind this project, and the synchronism of last weeks, which has made us think that this is just the beginning. In 1984, the Four Worlds International Institute published The Sacred Tree. Reflections on Native American Spirituality. In the first chapter, we can read the following story:

The ancient ones taught us that the life of the Tree is the life of the people. If the people wander far away from the protective shadow of the Tree, if they forget to seek the nourishment of its fruit, or if they should turn against the Tree and attempt to destroy it, great sorrow will fall upon the people. The people will lose their power. They will cease to dream dreams and see visions. They will begin to quarrel among themselves over worthless trifles. They will become unable to tell the truth and to deal with each other honestly. They will forget how to survive in their own land. Their lives will become filled with anger and gloom. Little by little they will poison themselves and all they touch.

It was foretold that these things would come to pass, but that the Tree would never die. And as long as the Tree lives, the people live. It was also foretold that the day would come when the people would awaken, as if from a long, drugged sleep; that they would begin, timidly at first but then with great urgency, to search again for the sacred Tree. (The Sacred Tree 7)

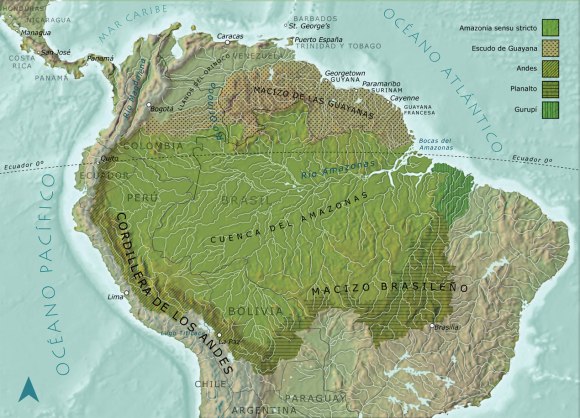

In the last decades, Indigenous Elders and advocates have been talking about the kinship trails across the Americas—the roots, the trunk and the branches of the Abya-Yala. We believe that all of the protagonists highlighted over the last twelve posts are recovering the vision of the Tree, and that the Indigenous World Forum on Water and Peace is part of the trails and crossroads of the Tree. Global mobilizations such as 2009 Mama Quta Titikaka, and Idle No More are part of the roots and fruits of the Tree. Current ceremonial exchanges among the Mayan Tatas and Amazonian Taytas are part of the roots and fruits of the Tree.

And this is probably the reason why the same text was used recently in documentary The Encounter of the Eagle and the Condor by Clement Guerra. In this astonishing project, the Elder Casey Camp read the story of The Sacred Tree while Nature spoke through the lens.

On September 27th, 2015, the night of the full moon eclipse, with the support of Indigenous Rising, Indigenous Environmental Network, Amazon Watch, Pachamama Alliance, and Rainforest Action Network, native women from the seven directions of Abya-Yala / Turtle Island met in New York and signed an Indigenous Women’s Treaty of the Americas. As we can learn from Defenders of Mother Earth–another piece by Guerra–Elder Casey Camp (Ponca Pa’tha’ta, USA), Patricia Gualinga (Sarayaku, Ecuadorian Amazon), Gloria Ushigua Santi (Sapara, Ecuadorian Amazon), Pennie Opal Plant (Yaqui/Choctaw/Cherokee, USA), Crystal Lameman (Beaver Lake Cree, Canada), and Blanca Chancoso (Kichua, Ecuadorian Andes) became family that day in a gesture of solidarity, creating a cross-border allegiance. A couple of months before the UN Climate Change Conference in Paris (COP 2015), the Indigenous Women’s Treaty of the Americas stated their demands to the world —100% renewable energy, the protection of the web of life, and to keep fossil fuels in the ground.

In tune with these trans-indigenous encounters, our friend Fredy Roncalla from Hawansuyo, sent us four poems by Omar Aramayo, a poet from the Titikaka Lake (Puno, Peru). One of them was entitled “The Water Battle”. And, a day after, Kim Shuck, Cherokee poet and contributor to the Indigenous Message on Water, sent us a poem entitled “War”. Neither of them knew about the synchronism! Immediately, we decided to translate the poems and include them in this sprout/post of the Tree. We hope that you enjoy them as much as we did!

Kim Shuck is a poet and visual artist of Tsalagi and Polish ancestry. Her first solo book, Smuggling Cherokee, won the Diane Decorah award in 2005 and was published by Greenfield Review Press. Her first book of prose, Rabbit Stories, came out in 2013 from Poetic Matrix Press. Kim is a founding member of the de Young Museum’s Native Advisory Board (San Francisco) and curates poetry events all over the Bay Area. She also edits the very irregular online journal Rabbit and Rose => http://kimshuck.com/

WAR

By K. Shuck

And in the water war we will

Paint signs of bravery and

Protection onto the

Salmon the

Trout and wade into the

Streams with them and they will

Paint us back in the

War of clear water we will

Insist that water be local and when it

Can’t be local we will weigh the benefit to the

Real costs of lawns in the

Desert or apricots and almonds we will

Seek to understand other people’s

Prayers and what gets flooded by

Dams or drained by canals and

Will consult the birds about the

Wetlands and they might paint us too and the

Consulting board will offer seats to pines and

Sunflowers who defended the people the

Last time and the wolves and beavers who change the

Streams will also be heard and we

Cannot lose cannot

Lose

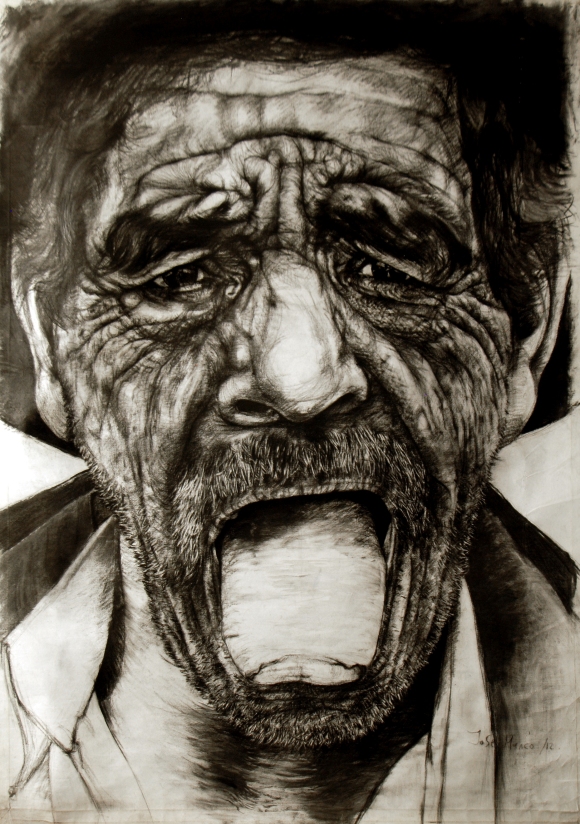

Omar Aramayo is an Andean poet, journalist, composer, and scholar. Since the 1960s, Omar has published experimental poetry, weaving music, visual arts and ancient traditions from the Titikaka Lake => http://poesiasdeomararamayo.blogspot.com/

THE BATTLE FOR WATER

By Omar Aramayo

Battle of people

battle of terror

the great battle of horror grabs us with stabs in the back

with kicks with bullets with toxic gases with electric nets

although we just realized it, it started a long time ago

the battle in which the word neighbor is broken eyelash by eyelash

cell by cell

an immense forest seeded with dead bodies from all species

the ocean in which the dead have sat down to have dinner

her servants assure they will bring to her every single living being

the keyboard of life has been broken overnight

a wave of sand rises in the wind

one behind the other

the water has gone with life

the survival of the species in the weight scale of doubt

those who are on the other side spit out in the face of life

the square is missing one of its sides

the circle is missing its equidistant center

intelligence has been used in the wrong way

being human has lost its meaning

its sacred side

has lost itself

the hearts of merchants are empty of god

they lie in their houses in front of their children

they lie in front of their wives

until they take their masks off

and their wives and children get in gear

in the name of wealth, the welfare

the personal finances

the order the power the prestige

someone tries to make us understand that this is in the name of the country

someone pops up in the screen speaking in the name of all

right now it’s necessary to know that we live in a country without tomorrow

the loggers the miners

the makers of big machines of big toxins

the city-factories set up on pirate ships

the bankers the politicians

those who sell everything in this time that everything is being sold

even the life they have sold

they have poisoned the earth

they have thrown ulcers on it

they have thrown dead on the water

the air is now full of monsters

lead flows through the children’s blood

elders die bleeding children are born idiotic

women scratch their sterile woumbs

this is the moment to put a stop

maybe there is still something beyond hope

hope is abandoned in the shores of the sea

like beached whales like birds or fish wrapped in plastic

Body of water mouth of water blue planet

other beings have emerged from the darkness

to kill you in the name of gold

to cut your neck as if you were the sweetest animal

of one stroke

an open pit

give us your word give us your blessing

your transparency where the fish glide

lit by the stars

give us the strength

in this battle of terror

What are you going to do city folk

women from plains and mountain ranges

child from the deserts who was just painted with a moon in the forehead

great lightning eye chief from the mountain

great medicine-men with a vegetal mother

teacher who swims toward the islands

agronomist who has lost the hat of the dreams

what are you going to do at this hour

I want to know I want you to tell us what is your role

you the irascible

and you who are a soul of god

in the great battle for water we are all the same

devil’s lawyer accountant who is cooking the books

you have been caught red-handed

facing bakwards painting a strange graffiti in the walls

lonely serpent eye which whistleling to the sun at noon

how are we going to stop the Dark One

the King Midas covered in gold in the center of a sea of shit

mud sand blowing without mercy

the salt period is coming

traces of the crime are planted everywhere

corpses of the criminals spread as cheap jewelry

hanging dry from their feet in the dust in the wind

the planet has been decimated due to lack of intelligence

of fine love

I want to hear your voice

I want to see your hands your chest

your sane intelligence resonating throughout the skies

so the planets might be touched

and the glaciers be dressed again and the streams be flowing full of health

(Translated by Fredy Roncalla and Juan G. Sánchez M.)

Although both poems paint an upside down world, where pollution and pain make us deaf and blind, both poems also envision a victory, where streams will be heard and glaciers will be dressed again. As Elder Josephine Mandamin asked us in our previous post, the main question remains: “what are you going to do city folk?”

Thank you for your patience and support for the past thirteen weeks. Thank you for sharing and spreading this message.

In humility,

Indigenous Message on Water

***

Mientras El árbol siga viviendo, la gente vivirá”: el encuentro entre el águila, el cóndor y el quetzal

Hoy queremos cerrar este ciclo con poesía y documental! Diseminando este mensaje intercultural de las últimas trece semanas, hemos tratado de construir puentes entre voces y luchas que están defendiendo el agua a lo largo y ancho del Abya-Yala y la Isla Tortuga. Hoy es especial porque vamos a compartir con ustedes una de las visiones que está detrás de este proyecto, además de las convergencias de los últimos días, las cuales nos han hecho pensar que esto es solo el comienzo. En 1984, el Instituto Internacional de los Cuatro Mundos publicó El árbol sagrado. Reflexiones sobre la espiritualidad nativo-americana. En el primer capítulo, encontramos la siguiente historia:

Los más antiguos nos enseñaron que la vida de El árbol es la vida de la gente. Si la gente deambula lejos de la sombra protectora de El árbol, si ellos olvidan buscar el alimento de su fruto, o si ellos se alzan en contra de El árbol e intentan destruirlo, gran pena caerá sobre ellos. La gente perderá su poder. Cesará de soñar y de tener visiones. Comenzará a pelear por nimiedadez sin valor. Llegará a ser incapaz de decir la verdad y de relacionarse con honestidad. Olvidará cómo sobrevivir en su propia tierra. Sus vidas llegarán a estar llenas de rabia y melancolía. Poco a poco la gente se envenenará a sí misma y a todo lo que toca.

(…) Se predijo que estas cosas sucederían, pero que El árbol nunca moriría. Y mientras El árbol siga viviendo, la gente vivirá. También se predijo que llegaría el día en que la gente se despertaría, como de un largo y pesado sueño; que la gente comenzaría, tímidamente al comienzo y después con gran urgencia, a buscar de nuevo El árbol sagrado… (The Sacred Tree 7)

En las últimas décadas, mayores, educadores y activistas indígenas han hablado sobre los senderos de parentesco entre los pueblos ancestrales que habitan las raíces, el tronco y las ramas del Abya-Yala / Isla Tortuga. Nosotros creemos que todos los protagonistas de los últimos doce posts están recobrando la visión de El gran árbol, y el Mensaje Indígena de Agua quisiera ser parte de este despertar. Movilizaciones globales como Mama Quta Titikaka en el 2009, o movimientos trans-indígenas como Idle No More son parte de las raíces y los frutos de El árbol. De igual forma, los intercambios ceremoniales que tatas mayas y taytas amazónicos han establecido en sus peregrinajes por fuera de su territorio ancestral, son parte de las raíces y los frutos de El árbol.

Y esta es probablemente la razón por la cual el mismo texto que citamos arriba fue usado recientemente en el documental The Encounter of the Eagle and the Condor, dirigido por Clement Guerra (2015). En este proyecto, la abuela Casey Camp lee la historia de El árbol sagrado mientras la naturaleza habla através del lente.

El 27 de septiembre de 2015, la noche del eclipse lunar, con el apoyo de Indigenous Rising, Indigenous Environmental Network, Amazon Watch, la Alianza Pachamama, y Rainforest Action Network, mujeres indígenas provenientes de las siete direcciones del Abya-Yala / la Isla Tortuga se encontraron en Nueva York y firmaron el Tratado de las Mujeres Indígenas de las Américas. Como se puede ver en Defensoras de la Madre Tierra – otro breve documental de Guerra – las mayores Casey Camp (Ponca Pa’tha’ta, USA), Patricia Gualinga (Sarayaku, Amazonía ecuatoriana), Gloria Ushigua Santi (Sapara, Amazonía ecuatoriana), Pennie Opal Plant (Yaqui/Choctaw/Cherokee, USA), Crystal Lameman (Beaver Lake Cree, Canadá), y Blanca Chancoso (Kichua, Andes ecuatorianos) decidieron crear una alianza más allá de las fronteras de los estados-nación, y convertirse así en familia en un gesto de solidaridad trans-indígena.

Unos meses antes de la Conferencia sobre Cambio Climático en París (COP 2015), el Tratado de las Mujeres Indígenas de las Américas dejó claro sus demandas para el mundo: 100% energía renovable, hay que dejar los combustibles fósiles bajo tierra, y ante todo la protección de la red de la vida.

Sintonizado con estos encuentros trans-indígenas, nuestro amigo Fredy Roncalla de la revista virtual Hawansuyo, nos envió cuatro poemas de Omar Aramayo, escritor del lago Titikaka (Puno, Perú), justo cuando estábamos redactando esta nota final. Uno de los poemas de Aramayo se titulaba “La batalla por el agua”. Y un día después, Kim Shuck, poeta Cherokee y colaboradora del Mensaje Indígena de Agua, nos envió a su vez un poema titulado “Guerra”. Por supuesto, ¡ninguno sabía acerca de estas confluencias! Inmediatamente, decidimos con Fredy traducir los poemas, los cuales compartimos aquí abajo para ustedes. Esperamos que los disfruten tanto como nosotros. ¡Gracias a Kim y a Omar!

Kim es poeta y artista visual de descendencia Tsalagi y Polaca. Su primer libro, Smuggling Cherokee, ganó el premio Diane Decorah en el 2005 y fue publicado por Greenfield Review Press. Su primer libro en prosa, Rabbit Stories fue publicado en el 2013 por Poetic Matrix Press. Kim es miembro fundador del consejo asesor indígena del Museo de Young (San Francisco) y organizadora de eventos de poesía en toda el Área de la Bahía de esta ciudad. Ella también edita la esporádica revista en-línea Rabbit and Rose. http://kimshuck.com/

GUERRA

K. Shuck

Y en la guerra por el agua

Pintaremos signos de valentía y

Protección sobre el

Salmón y la

Trucha y nos meteremos con ellos de

Cabeza en las corrientes y ellos nos

Pintarán de vuelta en la

Guerra por el agua clara nosotros

Insistiremos que el agua sea del lugar y cuando

No lo sea tantearemos el beneficio con el

Costo real de prados en el

Desierto o melocotones y almendras

Buscaremos entender los rezos de

Otros pueblos y qué se inunda por

Represas o se drena por canales y

Preguntaremos a los pájaros acerca de

Los pantanos y puede que ellos tambien nos pinten y el

Consejo de guías ofrecerá curules para los pinos y

Los girasoles que defendieron a las gentes la

Última vez y los lobos y los castores que cambian las

Corrientes también serán escuchados y nosotros

No podremos perder no podremos

Perder

(Traducción Fredy Roncalla y Juan G. Sánchez M.)

Omar Aramayo es poeta, periodista, compositor y académico de los Andes peruanos. Desde los años sesenta, ha creado un estilo singular en el que teje poesía, música, artes visuales y tradiciones ancestrales del lago Titikaka. https://hawansuyo.com/2016/05/13/cinco-poemas-del-agua-omar-aramayo/

LA BATALLA POR EL AGUA

Por Omar Aramayo

La batalla de los pueblos

la batalla del espanto

la gran batalla del horror nos toma a puñaladas por la espalda

a puntapiés a balazos a gases tóxicos a redes electrónicas

hace tiempo que ha comenzado aunque hoy recién nos percatamos

la batalla donde se quiebra la palabra prójimo pestaña a pestaña

célula a célula

un inmenso bosque sembrado de cadáveres de todas las especies

el océano donde la muerte se ha sentado a cenar

sus sirvientes aseguran con entregarle a todo ser viviente

el teclado de la vida se ha roto de la noche a la mañana

una ola de arena se levanta en el viento

una detrás de otra

el agua se ha ido con la vida

la supervivencia de las especies en la balanza de la duda

los que están al otro lado escupen en el rostro de la vida

al cuadrado le falta uno de sus lados

al círculo su centro equidistante

la inteligencia ha sido usada en sentido contrario

el ser humano ha perdido sentido

su lado divino

se ha perdido a sí mismo

los comerciantes tienen los corazones vacíos de Dios

en sus casas frente a sus pequeños hijos mienten

frente a sus mujeres mienten

hasta que se quitan las máscaras

y los hijos y las mujeres entran al engranaje

en nombre de la riqueza el bienestar

las finanzas personales

el prestigio el poder el orden

alguien intenta hacernos creer que es en nombre del país

alguien aparece en la pantalla en nombre de todos

es necesario saber ahora que vivimos en un país sin mañana

los taladores de bosques los mineros

los fabricantes de grandes máquinas de los grandes tóxicos

las factorías ciudades montadas sobre barcos piratas

los banqueros los políticos

los que venden todo en este tiempo en que todo se vende

hasta la vida han vendido

han envenado la tierra

le han echado llagas

le han echado muerte al agua

el aire se ha llenado de monstruos

por la sangre de los niños corre plomo

los niños nacen tarados los viejos mueren desangrados

las mujeres se arañan las entrañas estériles

es el momento de ponerles alto

tal vez queda algo más allá de la esperanza

la esperanza está botada en la ribera de los mares

como ballenas varadas como los peces o las aves forradas de plástico

Cuerpo de agua boca de agua planeta azul

otros seres han salido de la oscuridad

a matarte en nombre del oro

a cortarte el cuello como si fueras el más tierno de los animales

de un solo tajo

a tajo abierto

danos tu palabra danos tu bendición

tu transparencia donde los peces se deslizan

a la luz de los astros

a la luz de ellos mismos

danos tu fuerza

en esta batalla del espanto

Qué vas a hacer hombre de las ciudades

mujer de los llanos y cordilleras

niño de los desiertos recién acabado de pintar con una luna sobre la frente

gran jefe ojo de rayo de monte adentro

gran shamán de la madre vegetal

maestro que braceas hacia las islas

ingeniero agrónomo que has perdido el sombrero del sueño

qué vas a hacer en esta hora

quiero saber quiero que nos digas cuál es tu papel

tú iracundo

y tú que eres un alma de Dios

en la gran batalla por el agua somos lo mismo

abogado del diablo contador que llevas cuentas paralelas

has sido descubierto con las manos en la masa

de espaldas pintando en los muros un grafiti muy extraño

ojo solitario de la serpiente que silbas al sol del mediodía

cómo vamos a detener al Oscuro

al rey Midas cubierto de oro al centro de un mar de materia fecal

fango arena que sopla sin piedad

se aproxima el tiempo de la sal

la huella del crimen está sembrada por todo sitio

los cadáveres de los criminales como joyas sin valor derramados

secos colgados de los pies en el polvo en el viento

el planeta ha sido abatido por falta de inteligencia

de amor fino

quiero escuchar tu voz

quiero ver tus manos tu pecho

tu sana inteligencia retumbar por todos los cielos

que los planetas se conmuevan

y otra vez se vistan los glaciares y las corrientes corran plenos de salud

A pesar de que ambos poemas pintan un mundo al revés, en donde la polución y el dolor nos han vuelto sordos y ciegos, ambos poemas vislumbran también una victoria, en donde las corrientes de agua se escucharán de nuevo y los glaciares se vestirán una vez más. Como la abuela Josephin Mandamin nos preguntaba en una de las entradas anteriores, la pregunta principal sigue intacta: ¿qué vamos a hacer nosotros, hombres, mujeres de la ciudad?

Gracias por su paciencia y apoyo en estas trece semanas. Gracias por compartir y diseminar el mensaje.

En humildad,

Mensaje Indígena de Agua

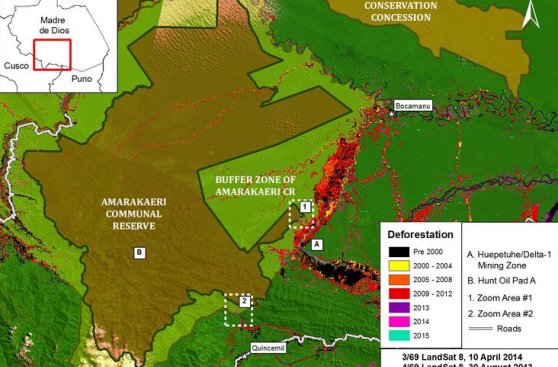

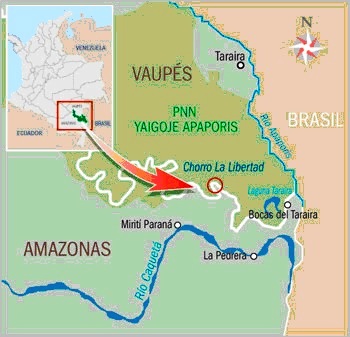

Amazonia. Map:

Amazonia. Map: